Software compilers play a crucial role in the programming ecosystem by converting high-level programming languages into machine code that computers can execute. Among the various functionalities they offer, the capability to integrate assembly language directly within high-level code stands out as particularly impactful. This feature empowers developers to blend the efficiency and control found in low-level programming with the abstraction and productivity characteristic of high-level languages. This document examines the history, functionality, and importance of compilers that support integrated assembly, exploring their mechanisms, application cases, and notable examples, supplemented by illustrative code snippets.

Understanding Compilers and Integrated Assembly

A compiler is a program responsible for translating source code written in a high-level programming language (e.g., C, C++, Pascal) into machine code or an intermediate representation executable by a computer’s processor. Assembly language, being a low-level programming language, offers a human-readable format of machine code, allowing direct control over hardware resources such as registers and memory.

Integrated assembly refers to the feature of a compiler that enables programmers to embed assembly language instructions directly within high-level code. This functionality is particularly beneficial for performance-critical applications, hardware interfacing, or situations where specific processor instructions must be conveyed that high-level languages cannot efficiently express. Compilers that support integrated assembly typically provide mechanisms like inline assembly or linking with external assembly files, facilitating seamless integration of both programming paradigms.

Historical Context

The incorporation of assembly language into high-level compilers arose as computer capabilities expanded and programming languages advanced. In the 1970s and 1980s, as languages like C gained traction, developers sought methods to optimize performance-intensive sections of code or interact directly with hardware, particularly in embedded systems and operating system development. Consequently, compilers began to include inline assembly to address these needs, striking a balance between abstraction and low-level control.

Prominent early compilers with assembly support include the Microsoft C Compiler (MSCC) for DOS, Borland’s Turbo C, and GNU’s GCC. These compilers were designed for environments with stringent resource constraints, such as early personal computers and embedded systems. As processor architectures evolved (e.g., x86, ARM), compiler support for inline assembly also became more advanced, accommodating a wider range of instruction sets and calling conventions.

Mechanisms of Integrated Assembly

Compilers that support integrated assembly typically employ two primary approaches:

- Inline Assembly: Assembly instructions are embedded directly within high-level code, using specific syntax or keywords. This allows developers to write assembly code alongside their high-level code, with the compiler managing the integration during the compilation process.

- Separate Assembly Modules: Developers create assembly code in separate files (commonly with a

.asmextension), which are compiled into object code and linked with high-level code. The compiler’s toolchain, including its assembler and linker, handles this integration.

Both methods necessitate that the compiler understands the target architecture’s instruction set and adeptly manages interactions between high-level variables and assembly-level registers or memory.

Inline Assembly

Inline assembly is generally implemented using specific syntax, such as the asm keyword in C/C++ compilers. The compiler processes these assembly blocks, translates them into machine code, and ensures proper integration with the surrounding code, including register allocation and stack management.

For instance, in GCC, inline assembly is written using the asm or __asm__ keyword, with a syntax that specifies inputs, outputs, and clobbered registers. This allows the compiler to optimize the code while adhering to the assembly instructions.

Separate Assembly Modules

When extensive assembly code is necessary, developers may write separate .asm files utilizing an assembler like NASM (Netwide Assembler) or MASM (Microsoft Macro Assembler). The compiler’s linker then combines the object files produced from these files with those generated from high-level code. This approach is prevalent in projects requiring substantial assembly routines, such as operating system kernels or device drivers.

Notable Compilers with Integrated Assembly Support

Several compilers are distinguished for their robust support of integrated assembly. Below, we examine some of the most prominent examples, their features, and applicable use cases.

1. GNU Compiler Collection (GCC)

GCC is a widely utilized compiler that supports multiple languages (C, C++, Fortran, etc.) and architectures (x86, ARM, RISC-V, etc.). Its inline assembly support, accessed using the asm keyword, is highly adaptable, enabling developers to specify constraints for inputs, outputs, and clobbered registers.

Example: Inline Assembly in GCC (x86 Architecture)

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int a = 10, b = 20, result;

// Inline assembly to add two numbers using x86 instructions

__asm__ (

"movl %1, %%eax;" // Move 'a' to EAX register

"addl %2, %%eax;" // Add 'b' to EAX

"movl %%eax, %0;" // Store result in 'result'

: "=r" (result) // Output

: "r" (a), "r" (b) // Inputs

: "%eax" // Clobbered register

);

printf("Result: %d\n", result); // Output: Result: 30

return 0;

}

In this example, the asm block utilizes x86 assembly to add two integers, a and b, storing the result in result. The syntax outlines outputs (=r), inputs (r), and clobbered registers (%eax), ensuring that the compiler effectively integrates the assembly.

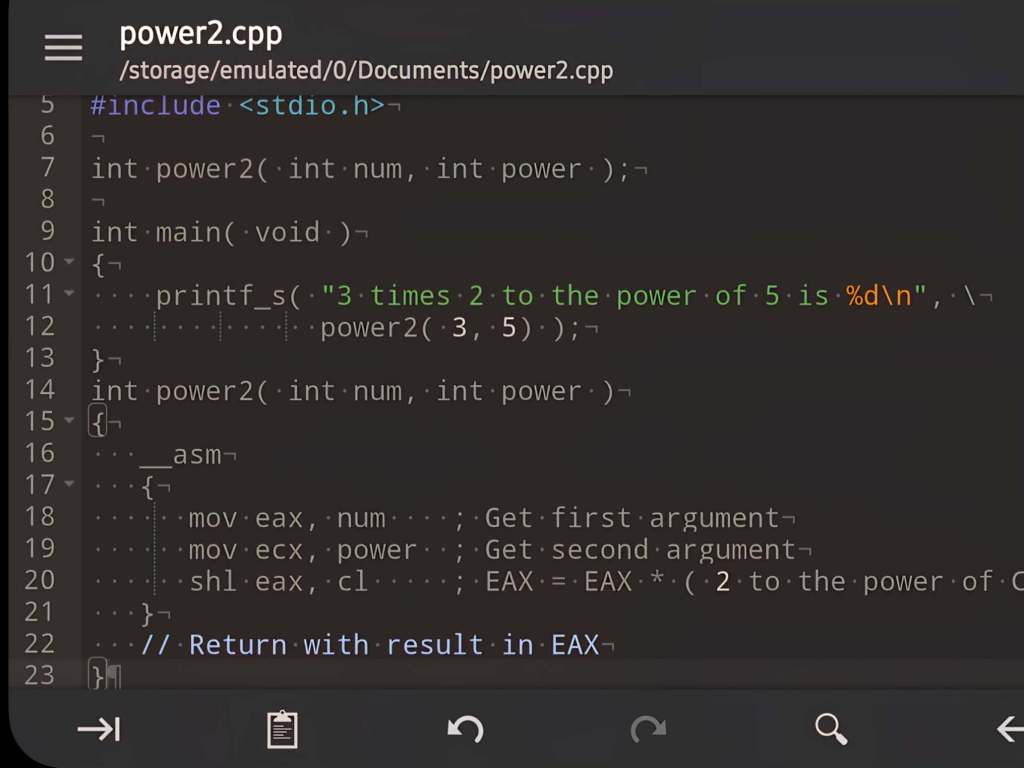

2. Microsoft C/C++ Compiler (MSVC)

Microsoft’s compiler, part of Visual Studio, accommodates inline assembly for x86 architectures using the __asm keyword. It is particularly favored in Windows development for system programming tasks or performance optimization. However, MSVC’s inline assembly support is restricted to 32-bit x86; for 64-bit architectures, developers must utilize separate .asm files with MASM.

Example: Inline Assembly in MSVC (x86)

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int a = 5, b = 10, result;

__asm {

mov eax, a ; Move 'a' to EAX

add eax, b ; Add 'b' to EAX

mov result, eax ; Store EAX in 'result'

}

printf("Result: %d\n", result); // Output: Result: 15

return 0;

}

This code conducts a similar addition operation as the GCC example but employs MSVC’s simplified syntax, obviating the need for explicit input/output constraints as the compiler directly assigns variables to registers or memory.

3. Borland Turbo C/C++

Borland’s Turbo C, prevalent during the 1980s and 1990s, was extensively used for DOS programming. It provided inline assembly support through the asm keyword, making it a preferred choice for developers crafting games or hardware drivers for early personal computers.

Example: Inline Assembly in Turbo C

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int a = 3, b = 7, result;

asm {

mov ax, a

add ax, b

mov result, ax

}

printf("Result: %d\n", result); // Output: Result: 10

return 0;

}

Turbo C’s inline assembly syntax is straightforward, resembling MSVC, and was designed for the 16-bit and 32-bit x86 architectures prominent at that time.

4. NASM and YASM with Compiler Integration

Although NASM (Netwide Assembler) and YASM are standalone assemblers, they are frequently utilized with compilers like GCC or MSVC to integrate separate assembly modules. Developers craft assembly code in .asm files, assemble them into object files, and link them with compiled high-level code.

Example: NASM Assembly with GCC

C File (main.c):

#include <stdio.h>

extern int add_numbers(int a, int b); // External assembly function

int main() {

int result = add_numbers(4, 5);

printf("Result: %d\n", result); // Output: Result: 9

return 0;

}

NASM File (add.asm):

; add.asm

section .text

global add_numbers

add_numbers:

push ebp

mov ebp, esp

mov eax, [ebp + 8] ; First argument (a)

add eax, [ebp + 12] ; Add second argument (b)

mov esp, ebp

pop ebp

ret

Compilation Commands:

nasm -f elf32 add.asm -o add.o

gcc -m32 main.c add.o -o program

This example illustrates how a separate assembly function (add_numbers) is scripted in NASM, assembled, and linked with a C program using GCC. The assembly code complies with the C calling convention, accessing function arguments via the stack.

Use Cases and Applications

Compilers equipped with integrated assembly support prove essential across various domains:

- Operating System Development: Kernels often necessitate low-level hardware access, such as interrupt handling or memory management, facilitated by inline assembly. For example, the Linux kernel extensively employs GCC’s inline assembly for architecture-specific code.

- Embedded Systems: In resource-constrained environments like microcontrollers, assembly can optimize performance or access specific hardware registers. Compilers such as GCC for ARM or AVR effectively support inline assembly for these purposes.

- Performance Optimization: In applications like game engines or scientific simulations, inline assembly can enhance critical loops or utilize specialized instructions (e.g., SIMD instructions like SSE or AVX).

- Device Drivers: Drivers require direct interaction with hardware, often relying on assembly for tasks like configuring registers or managing interrupts.

- Reverse Engineering and Security: Inline assembly is instrumental in tools designed for analyzing or modifying machine code, including debuggers or exploit development frameworks.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite its power, integrated assembly presents several challenges:

- Portability: Assembly code is specific to architecture, making programs less portable across different processors (e.g., x86 vs. ARM).

- Complexity: Writing and debugging inline assembly demands a comprehensive understanding of the target architecture and compiler conventions.

- Maintenance: Assembly code is often harder to read and maintain than high-level code, potentially increasing development costs.

- Compiler Limitations: Certain compilers (e.g., MSVC) restrict inline assembly to specific architectures or mandate separate assembly files for others, complicating workflows.

Modern compilers often address these issues by offering intrinsics—high-level functions that correspond to specific assembly instructions—minimizing the need for raw assembly while preserving performance.

The Future of Integrated Assembly

As processors progress and high-level languages enhance, the necessity for inline assembly has lessened in certain contexts. Modern compilers generate highly optimized machine code, and intrinsics allow access to specialized instructions without requiring assembly. Nevertheless, integrated assembly retains its relevance in areas such as embedded systems, real-time applications, and low-level system programming.

Emerging architectures like RISC-V and advancements in compiler technologies (e.g., LLVM) continue to support inline assembly, ensuring its ongoing utility for developers. Additionally, tools like JIT (Just-In-Time) compilers, which dynamically create machine code, frequently rely on assembly-like constructs for performance-critical operations.

Conclusion

Compilers with integrated assembly support effectively bridge the gap between high-level abstraction and low-level control, enabling developers to harness hardware capabilities when necessary. From GCC’s versatile inline assembly to MSVC’s x86 support and NASM’s modular approach, these tools have influenced system programming, embedded development, and performance optimization. While challenges regarding portability and complexity remain, the capacity to embed assembly within high-level code is a fundamental aspect of low-level programming. As technology continues to advance, compilers facilitating integrated assembly will evolve, ensuring that developers can maintain a balance between productivity and precision in an ever-changing technological landscape.