In the field of software engineering, the adage “less is more” often encourages developers to produce concise and readable code that emphasizes simplicity and maintainability. However, this principle does not always hold in scenarios where performance is a primary concern. In certain cases, implementing a more verbose algorithm—using additional lines of code—can result in superior efficiency compared to a more streamlined solution.

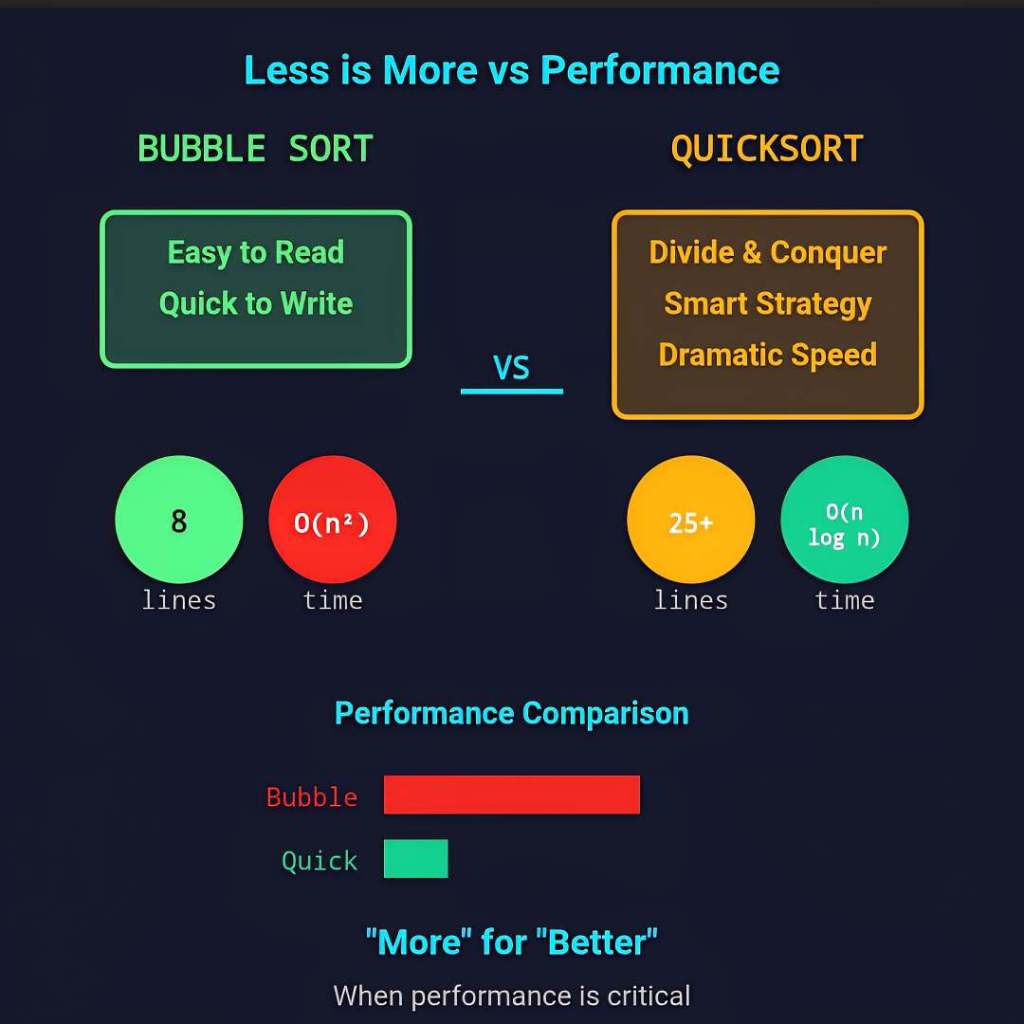

To illustrate this concept, consider the task of sorting an array of integers using two different algorithms implemented in C: the straightforward but less efficient Bubble Sort, and the more complex yet highly performant QuickSort. This discussion explores how a more detailed algorithm can deliver better performance, thereby challenging the assumption that minimizing code is always optimal.

The Task: Sorting an Array

Sorting an array of integers is a fundamental operation with applications across data processing, search algorithms, and user interfaces. The objective is to arrange the integers in ascending order. For the purposes of this analysis, we examine a large dataset and compare two algorithms: Bubble Sort, known for its simplicity, and QuickSort, recognized for its efficiency despite its increased complexity and length.

Bubble Sort: A Simple Approach

Bubble Sort is among the simplest sorting algorithms and is often introduced early in programming education. It works by repeatedly passing through the array, comparing adjacent elements, and swapping them if they are out of order. This process continues until the array is sorted. The implementation in C is as follows:

void bubble_sort(int arr[], int n) {

int i, j, temp;

for (i = 0; i < n - 1; i++) {

for (j = 0; j < n - i - 1; j++) {

if (arr[j] > arr[j + 1]) {

temp = arr[j];

arr[j] = arr[j + 1];

arr[j + 1] = temp;

}

}

}

}

This code is relatively short, typically less than 15 lines, and easy to understand. However, it suffers from poor performance, with a worst-case and average time complexity of O(n²). For large datasets—such as an array with 10,000 elements—Bubble Sort performs approximately 100 million comparisons and swaps, making it impractical for large-scale applications. Its simplicity leads to redundant comparisons, especially when the array is nearly sorted.

QuickSort: A More Complex but Efficient Solution

In contrast, QuickSort employs a divide-and-conquer strategy. It selects a pivot element, partitions the array into subarrays of elements less than and greater than the pivot, and recursively sorts these subarrays. Here’s an example implementation in C:

void swap(int* a, int* b) {

int temp = *a;

*a = *b;

*b = temp;

}

int partition(int arr[], int low, int high) {

int pivot = arr[high];

int i = low - 1;

int j;

for (j = low; j < high; j++) {

if (arr[j] <= pivot) {

i++;

swap(&arr[i], &arr[j]);

}

}

swap(&arr[i + 1], &arr[high]);

return i + 1;

}

void quick_sort(int arr[], int low, int high) {

if (low < high) {

int pivot_index = partition(arr, low, high);

quick_sort(arr, low, pivot_index - 1);

quick_sort(arr, pivot_index + 1, high);

}

}

This implementation spans more than 30 lines due to auxiliary functions and recursion. Despite its length, QuickSort boasts an average-case time complexity of O(n log n), a significant improvement over Bubble Sort. For a dataset of 10,000 elements, QuickSort typically performs on the order of 100,000 operations—about 1,000 times fewer than Bubble Sort. This efficiency stems from partitioning, which reduces the number of comparisons by focusing on elements relative to the chosen pivot.

The Advantages of More Complex Algorithms

The superior performance of QuickSort illustrates how a more detailed implementation can outperform simpler algorithms. The additional code enables several important optimizations:

- Efficient Divide-and-Conquer Strategy: QuickSort employs recursive partitioning to divide the problem into smaller subarrays, reducing the number of comparisons needed. Each recursive call handles a smaller subset, resulting in a logarithmic depth of recursion. In contrast, Bubble Sort relies on repeatedly scanning the entire array without such strategic division.

- Reduced Redundant Comparisons: The

partitionfunction reorganizes elements around a pivot, limiting the number of comparisons each element undergoes across recursive calls. Bubble Sort’s nested loops compare adjacent elements multiple times, leading to unnecessary operations. - Better Scalability: QuickSort performs well with large datasets, with an average complexity of O(n log n). Bubble Sort’s O(n²) complexity makes it inefficient for sizable inputs. Implementing advanced techniques like median-of-three pivot selection can further enhance QuickSort’s performance by minimizing the risk of worst-case scenarios, albeit with additional code.

The extra lines of code in QuickSort embody a sophisticated approach that minimizes computational overhead, making it significantly more effective for large-scale data.

Considerations of Readability and Maintenance

While QuickSort offers excellent performance, its increased complexity can pose challenges. Bubble Sort’s straightforward implementation makes it easier to understand and debug, particularly for small datasets (e.g., fewer than 100 elements), where performance differences are negligible. Conversely, QuickSort’s recursive nature and pointer manipulations — especially in languages like C — increase the potential for errors such as off-by-one mistakes or stack overflows if not carefully optimized (for example, by switching to iteration for small subarrays). Additionally, the possibility of worst-case O(n²) behavior, often mitigated through randomized pivot selection, introduces further complexity.

Practitioners must balance the need for efficiency with the importance of maintainability. For small-scale tasks, simplicity may suffice; however, for systems processing millions of records, the performance benefits of QuickSort are often justified despite the added complexity. Many real-world sorting libraries, such as C’s qsort, incorporate hybrid methods combining multiple algorithms to optimize for a variety of input scenarios, resulting in more intricate code but better overall performance.

Broader Implications

The comparison between Bubble Sort and QuickSort highlights that in software engineering, the “less is more” philosophy does not always apply. While concise code is desirable for clarity and ease of maintenance, achieving optimal performance sometimes necessitates more elaborate implementations. This principle extends beyond sorting algorithms:

- Graph Algorithms: Dijkstra’s algorithm, though more complex than breadth-first search, provides efficient shortest-path calculations in weighted graphs.

- Data Structures: Red-black trees involve extensive code but offer operations with guaranteed logarithmic complexity.

- Caching Strategies: Implementing advanced cache eviction policies like Least Recently Used (LRU) increases complexity but dramatically enhances performance in repeated computations.

In each case, the additional code often encodes key optimizations that substantially reduce runtime at the expense of increased implementation complexity.

Final Remarks

While concise, maintainable code is a cornerstone of good software engineering, performance-critical applications often benefit from more detailed algorithms. QuickSort’s efficiency demonstrates how added lines of purposeful code, utilizing techniques such as divide-and-conquer, can lead to significant performance improvements. Developers should weigh the trade-offs carefully: simplicity for small or non-performance-sensitive tasks, and complexity when handling large-scale, demanding systems. Ultimately, in software development, sometimes “more” is the necessary investment to achieve “better” results.