The Logo programming language, developed in the late 1960s by Seymour Papert, Wally Feurzeig, and others at MIT, is often recognized for its iconic turtle graphics, wherein a virtual “turtle” draws shapes on a screen by executing simple commands such as FORWARD, RIGHT, and LEFT. While Logo may appear as a relic of early computing, primarily intended for educational purposes, its foundational principles and philosophy continue to impart significant lessons for contemporary software engineers and the development of programming tools. Rooted in constructivist learning theory, Logo was designed to promote creativity, problem-solving, and a comprehensive understanding of computational thinking. This essay examines how Logo’s core principles—simplicity, interactivity, accessibility, and exploratory learning—can serve as inspiration for modern software engineers and influence contemporary programming tool design.

Simplicity as a Design Principle

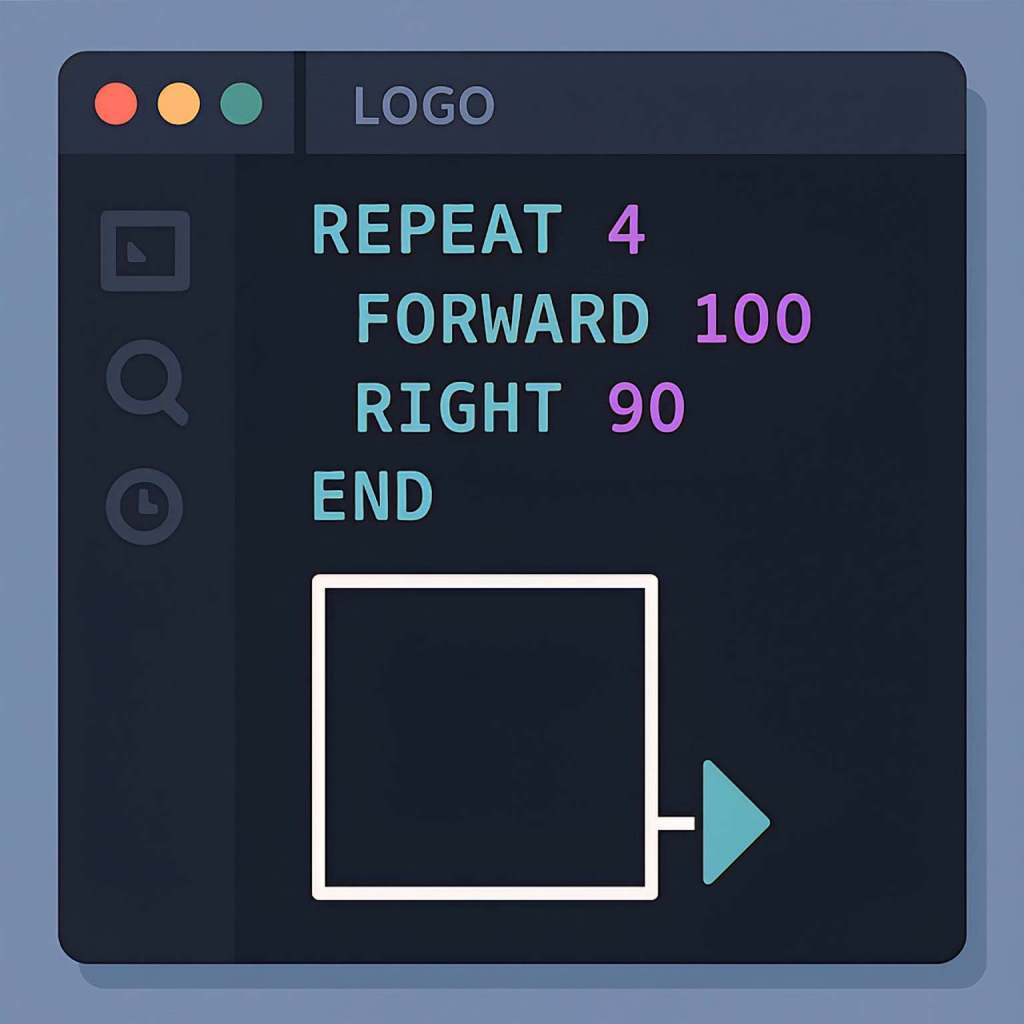

One of Logo’s most enduring lessons highlights the value of simplicity in programming languages and tools. Logo’s minimal syntax and intuitive commands enable beginners to create intricate patterns and behaviors with minimal code, exemplified by a simple sequence like REPEAT 4 [FORWARD 100 RIGHT 90], which draws a square and establishes an immediate connection between code and output.

Lessons for Modern Software Engineers: In an era characterized by increasingly complex frameworks and software systems, Logo serves as a reminder for engineers to prioritize simplicity. The popularity of modern languages like Python and JavaScript can be attributed, in part, to their approachable syntax, akin to Logo. Engineers can draw inspiration from Logo to develop APIs, libraries, and tools that are intuitive and minimize cognitive load. For instance, frameworks like React emphasize declarative programming, allowing developers to describe what they want rather than how to achieve it, resonating with Logo’s focus on clear, high-level commands.

Tooling Implications: Logo’s emphasis on simplicity encourages contemporary tools to prioritize user-friendly interfaces and minimalistic design. Integrated Development Environments (IDEs) such as Visual Studio Code or Jupyter Notebooks emphasize clean interfaces and immediate feedback, mirroring Logo’s turtle graphics environment. Tools that offer instant visual or interactive output—such as live code reloading in web development or real-time data visualization in Jupyter—reflect Logo’s philosophy of making programming accessible and engaging.

Interactivity and Immediate Feedback

Logo’s turtle graphics provided immediate visual feedback, allowing users to observe the results of their code in real time as the turtle traversed the screen. This interactivity was groundbreaking, facilitating experimentation, mistake-making, and rapid iteration. The tight feedback loop promoted a sense of agency and curiosity, in line with Papert’s vision of “learning by doing.”

Lessons for Modern Software Engineers: The significance of rapid feedback loops is foundational in modern software development practices. Agile methodologies, continuous integration/continuous deployment (CI/CD) pipelines, and test-driven development (TDD) all emphasize quick iteration and validation, similar to Logo’s immediate visual output. Engineers can learn from Logo to design systems that provide timely and actionable feedback, reducing the friction between coding and result observation. For example, hot-reloading in frameworks like Vite or Next.js enables developers to see UI changes instantly, echoing Logo’s responsive design.

Tooling Implications: Logo’s interactive nature has influenced modern development environments. Tools such as REPLs (Read-Eval-Print Loops) in Python or Node.js, browser developer consoles, and interactive playgrounds (e.g., CodePen, JSFiddle) offer real-time feedback, fostering experimentation reminiscent of Logo’s turtle graphics. Additionally, modern debugging tools featuring live variable inspection or time-travel debugging (e.g., Redux DevTools) reflect Logo’s emphasis on making the effects of code visible and comprehensible. These tools promote exploratory programming, enabling engineers to test hypotheses and learn through trial and error.

Accessibility and Inclusive Design

Logo was created to be accessible to children and non-programmers, embodying Papert’s belief that anyone can engage with computational ideas. Its intuitive commands and forgiving syntax lowered barriers to entry, presenting programming as a creative endeavor rather than an esoteric skill.

Lessons for Modern Software Engineers: Logo’s accessibility challenges engineers to create software that is inclusive and approachable for diverse audiences. This is particularly relevant in open-source communities, where clear documentation and beginner-friendly contribution paths are essential. Modern languages such as Scratch (a direct descendant of Logo) and Blockly continue this tradition by utilizing visual programming to make coding accessible to children and non-technical users. Software engineers can apply this principle by designing user interfaces, APIs, and documentation that cater to users with varying levels of expertise.

Tooling Implications: Logo’s influence is apparent in tools developed for education and onboarding. Platforms like Replit, Glitch, and Codecademy provide low-barrier environments where beginners can experiment with code without complex setup processes. Visual programming tools, such as Node-RED or Unreal Engine’s Blueprints, draw from Logo’s legacy, enabling non-programmers to create logic flows visually. These tools democratize software development, aligning with Logo’s mission to make programming universally accessible.

Exploratory Learning and Creativity

Logo represented not merely a programming language but a philosophy of learning. Papert’s constructivist approach encouraged users to explore, experiment, and build their understanding of programming concepts. By creating spirals, fractals, or games, users learned recursion, iteration, and abstraction through active exploration rather than rote memorization.

Lessons for Modern Software Engineers: Logo’s exploratory ethos inspires engineers to embrace creativity and experimentation in their work. In contemporary software development, this translates to prototyping, hackathons, and iterative design processes. Engineers can draw from Logo to approach problems with a playful mindset, utilizing tools such as sandboxes or proof-of-concept projects to test ideas before committing to production code. This mindset aligns with the growing emphasis on creative coding, where engineers use languages like Processing or p5.js to blend programming with art, reminiscent of Logo’s turtle graphics.

Tooling Implications: Logo’s influence is evident in tools that promote experimentation and creativity. Game development engines like Unity or Godot offer sandboxes where developers can rapidly prototype ideas, akin to Logo’s canvas. Similarly, data science tools like Jupyter Notebooks enable users to explore datasets interactively, iterating on code and visualizations in a Logo-like manner. These tools foster a mindset of discovery, where the process of building and refining is as important as the final product.

Abstraction and Modularity

Logo introduced users to powerful programming concepts, such as procedures, recursion, and modularity, in an accessible manner. For instance, users could define a procedure like TO SQUARE :SIZE to encapsulate the logic for drawing a square, enabling reuse with various parameters. This highlighted the importance of abstraction—dividing complex problems into reusable components.

Lessons for Modern Software Engineers: Abstraction and modularity are foundational principles of contemporary software engineering. Logo’s method of procedures anticipates concepts such as functions, components, and microservices in today’s programming landscape. Engineers can learn from Logo to design systems that are modular, reusable, and composable, thereby reducing complexity and enhancing maintainability. For example, the component-based architecture of React or Vue.js reflects Logo’s idea of creating reusable building blocks.

Tooling Implications: Modern tools place significant emphasis on modularity. Package managers like npm or pip enable developers to share and reuse code modules, akin to Logo’s procedures. Containerization tools such as Docker and orchestration platforms like Kubernetes facilitate modular deployment, encapsulating services in a manner echoing Logo’s procedural abstraction. These tools simplify the construction of complex systems from simple, reusable components, a principle Logo championed decades ago.

Influence on Educational Tools and Computational Thinking

Perhaps Logo’s greatest contribution is its role in shaping computational thinking—the ability to decompose problems, design algorithms, and think systematically about solutions. Papert envisioned computational thinking as a universal skill, applicable not only to programmers but to all individuals. Logo’s influence is evident in modern educational initiatives like Code.org, Hour of Code, and the increasing number of coding bootcamps.

Lessons for Modern Software Engineers: Logo reminds engineers that programming extends beyond writing code to encompass creative and systematic problem-solving. This perspective is vital in fields such as data science, machine learning, and systems design, where disaggregating complex problems into manageable tasks is crucial. Engineers can adopt the playful, problem-solving mindset exemplified by Logo to approach challenges in innovative ways.

Tooling Implications: Logo’s educational legacy has inspired a new generation of tools tailored to teach computational thinking. Platforms such as Scratch, Tynker, and Alice employ visual metaphors (often inspired by Logo’s turtle) to introduce programming concepts to children. For professional developers, tools such as LeetCode or HackerRank gamify problem-solving, encouraging similar algorithmic thinking fostered by Logo. These tools bridge the gap between education and professional practice, ensuring that computational thinking remains an essential skill.

Challenges and Limitations

While the principles of Logo are inspiring, it is important to recognize its limitations. Logo was created for educational purposes rather than production systems, and its simplicity can feel constraining for complex applications. Modern software engineering often demands scalability, performance, and robustness, which Logo was not designed to address. However, these limitations underscore the importance of context: Logo’s strengths lie in teaching foundational concepts, rather than serving as a general-purpose language.

For contemporary engineers, the challenge lies in balancing Logo’s simplicity and accessibility against the demands of production environments. Tools such as TypeScript or Go, which merge simplicity with robustness, reflect efforts to address this gap. Similarly, tooling must navigate the balance between ease of use and the capacity to manage complex workflows, as observed in the evolution of IDEs from basic text editors to advanced environments like JetBrains IntelliJ.

Conclusion

The Logo programming language, although rooted in the educational context of the 1960s, provides enduring lessons for modern software engineers and tool developers. Its focus on simplicity, interactivity, accessibility, exploratory learning, and modularity resonates with today’s programming paradigms and tools. From the immediate feedback of turtle graphics to the modularity of procedures, the principles of Logo are mirrored in contemporary practices like agile development, component-based architectures, and interactive development environments. By embracing Logo’s philosophy, software engineers can design systems that are intuitive, inclusive, and conducive to creativity, while tool developers can create environments that empower users to explore, learn, and innovate. In an increasingly complex technological landscape, Logo’s legacy serves as a reminder that the essence of programming lies in making the abstract tangible, simplifying the complex, and ensuring that the act of creation remains accessible to all.